You Were Made For Rest (#21)

What the Sabbath Means for 21st Century Workers

In 2019, the Japanese government launched a nationwide campaign called Premium Friday. On the last Friday of every month, employees were encouraged to leave work at 3 p.m., freeing the afternoon for shopping, family time, or rest. The idea was to reduce stress, spark consumer spending, and chip away at the country’s infamous culture of karoshi, or death from overwork. For a brief moment, it seemed like a small revolution against Japan’s grinding productivity machine. But the campaign quickly lost steam. Many employees admitted they were afraid to leave early. Bosses frowned on it. Deadlines loomed. The culture of production swallowed the attempt whole.

The short-lived Japanese experiment reveals something larger. Our problem isn’t just long hours or poor policies; it’s an inability to rest. We’ve forgotten what it means to live as if rest had value in itself, and not only production.

The Problem of Constant Production

Modern workers, from coders to professors to technical writers, swim in the same water. Output defines worth. Did you close the ticket? Update the wiki? Answer the Slack message before the ping grew stale? The pressure is constant, and the pace unforgiving. If you can’t keep up, you risk becoming irrelevant. The result is a life lived on the edge of exhaustion.

Documentation itself often bears the marks of this fatigue. Pressed for time, writers settle for shallow drafts, recycling old text and skipping the work of true orientation. The outcome may be technically correct, but it lacks depth and direction. Exhaustion breeds mediocrity. And worse, it breeds the suspicion that this is simply the way life has to be.

But what if it doesn’t?

Sabbath as Resistance

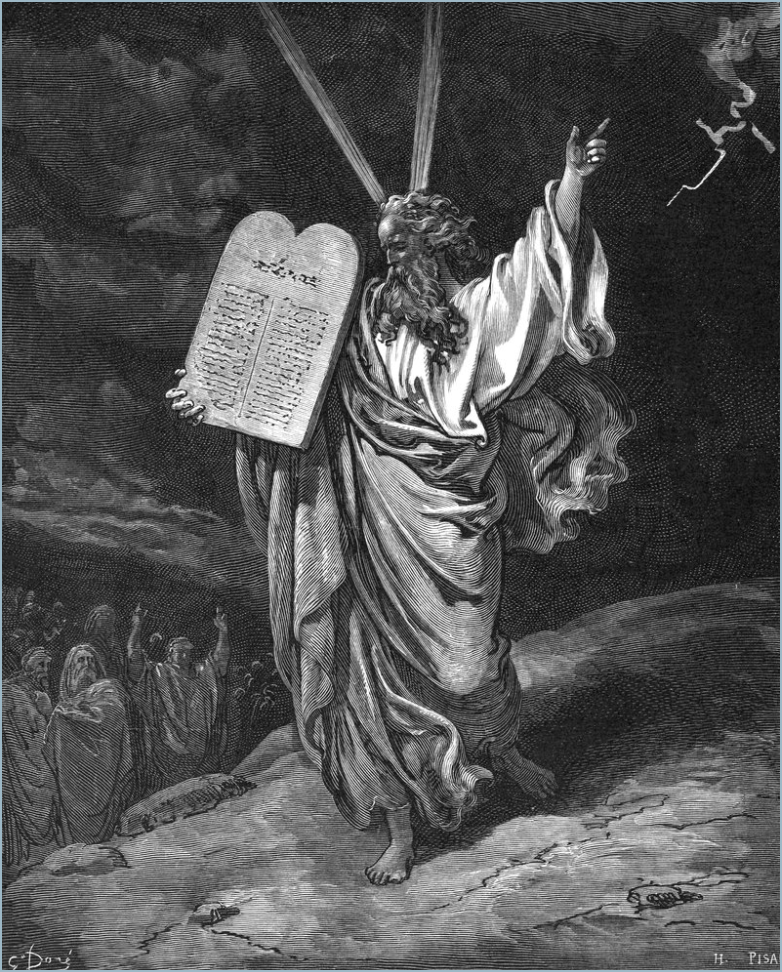

As Moses descends from Mount Sinai, he carries a tablet with these words etched on it (Exodus 20:8-11):

Remember the Sabbath day by keeping it holy. Six days you shall labor and do all your work, but the seventh day is a sabbath to the Lord your God. On it you shall not do any work, neither you, nor your son or daughter, nor your male or female servant, nor your animals, nor any foreigner residing in your towns. For in six days the Lord made the heavens and the earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but he rested on the seventh day. Therefore the Lord blessed the Sabbath day and made it holy.

In our context, the Sabbath can seem like a Puritanical restriction – a stale, legalistic requirement that seems out-of-touch with the modern world. But the Sabbath speaks toward a truth that we can miss without the proper framing.

When the Hebrew Bible introduces the command to rest on the last day of the week, it does so against the backdrop of slavery. The Hebrews had just been liberated from Pharaoh’s economy, a chattel system where their only value was measured in bricks and barley. Under Pharaoh, the Hebrew people existed to produce goods, and their oppressors were endlessly hungry for more.

In this setting, the command to rest shifts from legalistic to subversive. The God of Israel was not a god who demanded constant production from helpless slaves. Rather, YHWH was a God who saw human need, tiredness, and limitation, and respected these realities. YHWH was a God of rest.

During university, I read Walter Brueggemann’s short book titled Sabbath as Resistance, in which he argues that the Sabbath served both as a resistance and an alternative to empire. The command to rest resisted imperial force because it declared that Israel would not be defined by production and consumption, against the will of occupying powers like Egypt, Babylon, or Rome. Even if Caesar wanted business to continue as normal all day, every day, Israel claimed for herself a slower, humane pace that left room for respite. In this way, Sabbath provided an alternative to the empire by carving out space for justice, neighborliness, and mercy in place of tireless, systematic abuse.

The Sabbath was never about some sanctimonious rite of devotion. It was a statement of identity. By resting, Israel declared that they were no longer slaves of Pharaoh but children of God.

In this context, rest is not merely idleness but intentional disengagement from production to recover strength, perspective, and freedom. And that kind of rest has everything to do with us.

Why This Matters for Documentation

Good documentation depends on clarity, perspective, and patience. It requires the writer to step back and see how instructions connect to larger meaning. But this ability is impossible without rest. If we live like Pharaoh’s slaves — producing endlessly with no pause — our words inevitably flatten, and so do we. We become lifeless because we are writing from a place of exhaustion.

Sabbath, or intentional rest, interrupts that cycle. It creates the space where words can breathe. It allows writers to return to their work with sharper questions:

What problem am I solving?

How does this task fit into the user’s larger journey?

Why does this matter?

Without rest, we can easily lose these questions, letting our documents drift toward soullessness.

This insight isn’t only theological; it’s psychological. A 2007 study by Sabine Sonnentag and Charlotte Fritz found that psychological detachment from work during leisure time predicts greater productivity, creativity, and well-being once employees return to their tasks. Rest does not compete with performance — it sustains it.

Practices for the Modern Writer

So what does it mean to practice Sabbath as a technical writer or knowledge worker today? It doesn’t require observing Saturday as sacred. But it does require carving out intentional rhythms of disengagement.

Here are four ways to begin:

Set real boundaries. Choose times when you will not check Slack, email, or tickets. Protect those times with the seriousness of a meeting.

Create rituals of renewal. For some, this is a weekly hike. For others, it’s a family meal or reading hour. The form matters less than the intention.

Work from overflow, not depletion. Begin writing projects after you have given yourself margin to reflect. This is the difference between words that guide and words that merely fill space.

Model rest for your team. Share openly about your boundaries. Normalize rhythms of disengagement so your peers see that sustainable work includes recovery.

Closing

Japan’s “Premium Friday” campaign failed because it tried to legislate what can only be practiced as a conviction. Sabbath begins not with permission but with belief: that you are more than what you produce. It’s a counter-narrative, an insistence that your worth is not tied to tickets closed, code shipped, or documents published.

Brueggemann is right. Sabbath is both resistance and alternative. It resists the hamster wheel of endless achievement, and it offers the alternative of life built on justice, neighborliness, and rest.

For technical writers — and for anyone trapped in the churn of modernity — the lesson is simple but costly: you were not made for Pharaoh’s storehouses. You were made for rest. And paradoxically, it is this rest that will give your words, and your work, their true power.

Written in memory of Walter Brueggemann (1933-2025), whose work helped sustain my Christian faith through a difficult time.