Resilience Redefined (#31)

Defining Your Role and Environment before the Chaos Hits

Most people talk about resilience like it’s a test of will: how much chaos, ambiguity, or rework you can absorb before you finally fracture.

But that’s not the kind of resilience technical writers need.

Technical writers don’t burn out from difficult work. They burn out from undefined boundaries. You get pulled in every direction. The scope of work expands without warning. You inherit missing context and contradictory inputs.

Then gradually, you become whatever your stakeholders need you to be. And in a rare moment of clarity, you catch yourself asking:

Why am I doing what I’m doing?

Why does the work no longer make sense?

Resilience begins before that point.

It begins with structure.

The Shape of Real Resilience

Resilience often gets described as a moral quality. It is something earned through hardship or displayed under pressure. But for technical writers, resilience isn’t heroism. It’s not toughness, endurance, or a willingness to power through.

Resilience is the ability to return to a coherent form after impact.

Having resilience gives you operational advantages:

Unshakeable under shifting requirements. When the product changes, you don’t panic.

Deeply valuable in ambiguous environments. When everyone else starts spiraling, you stay grounded and teams notice.

Less susceptible to burnout. A stable shape can prevent burnout that results from trying to be all things to all people.

In a 2024 study of over 2,000 firefighters, researchers found that those with high self-concept clarity — a well-defined, coherent sense of identity — were significantly more resilient and far less likely to experience burnout.

The researchers concluded that “self-concept clarity can not only directly affect the working state... but can also influence job burnout and improve work engagement through the mediating effect of resilience”.

You build resilience while things are calm. And you build it by defining who you are and designing conditions that let you stay that way. But before we can build it, we need to understand what resilience actually is.

Why We Don’t Think of Resilience This Way

If resilience is really structural — a product of self-definition and environment — then why don’t more writers see it that way?

Part of the problem is framing. We’ve been taught to think of resilience as a personal virtue:

Calm under pressure

Patience with ambiguity

Endurance when timelines compress or scope expands

Under that lens, resilience becomes a matter of character. You either have it or you slowly develop it through repetition, strain, and the right mix of self-regulation techniques.

When the strain shows, the response is always inward: breathe, adjust your attitude, manage your energy, take a nap. This isn’t bad advice, but it’s incomplete.

The environments we operate in don’t just challenge us. They define us. And most technical writers have been conditioned to adapt to that definition. We’ve been rewarded for absorbing ambiguity, for filling in the gaps, for being helpful in ways that quietly exceed the shape of the role itself.

As we keep absorbing this ambiguity, we condition ourselves to believe that this is resilience: the willingness to stretch further than we should, to recover without complaint, to stay upright no matter how many inputs contradict each other.

But that’s not resilience. That’s distortion.

The corrective starts with self-definition.

Self-Definition: Your Shape

Technical writing attracts conscientious people — thoughtful people who take pride in being useful and who quietly shape their identity around being dependable. These are strengths, until they aren’t. Because over time, usefulness can start to replace definition.

Early in my career, I began to notice a pattern. The writers who struggled most weren’t the ones with the weakest skills or shallowest experience. They were the ones who lacked a defined shape. They stepped into every gap. They treated every request like a mandate. They believed their job was to be helpful.

And when things inevitably got messy — shifting requirements, clashing stakeholder inputs, unexpected fire drills — they had nothing to return to. No fixed center. No grounding principle. Just a slowly expanding tangle of obligations they never actually agreed to.

Most engineers can explain the constraints that shape their architecture. PMs can articulate what they’re optimizing for. Designers, analysts, even sales leads tend to have some north star for their work.

That’s why self-definition isn’t a branding exercise or a manifesto. It’s a structural necessity. And often, it’s private.

“I transform raw technical intent into usable information. I don’t generate that intent myself.”

“My value is clarity, context, and coherence — not inventing features, rewriting roadmaps, or rescuing broken processes.”

These are quiet lines. But they change everything.

Because once you define your shape, the work starts to stabilize. You stop reacting to every new ask. You start making deliberate choices. And the people around you begin to follow your lead, often without even realizing it.

Resilience begins here.

However, self-definition only matters if the environment reinforces it.

Environment: The Structure Around the Shape

You can be clear about your role. You can know the shape you’re meant to hold. But if everything around you tugs at that shape with incomplete inputs, mismatched expectations, or an endless drip of undocumented edge cases, the clearest self-definition starts to blur.

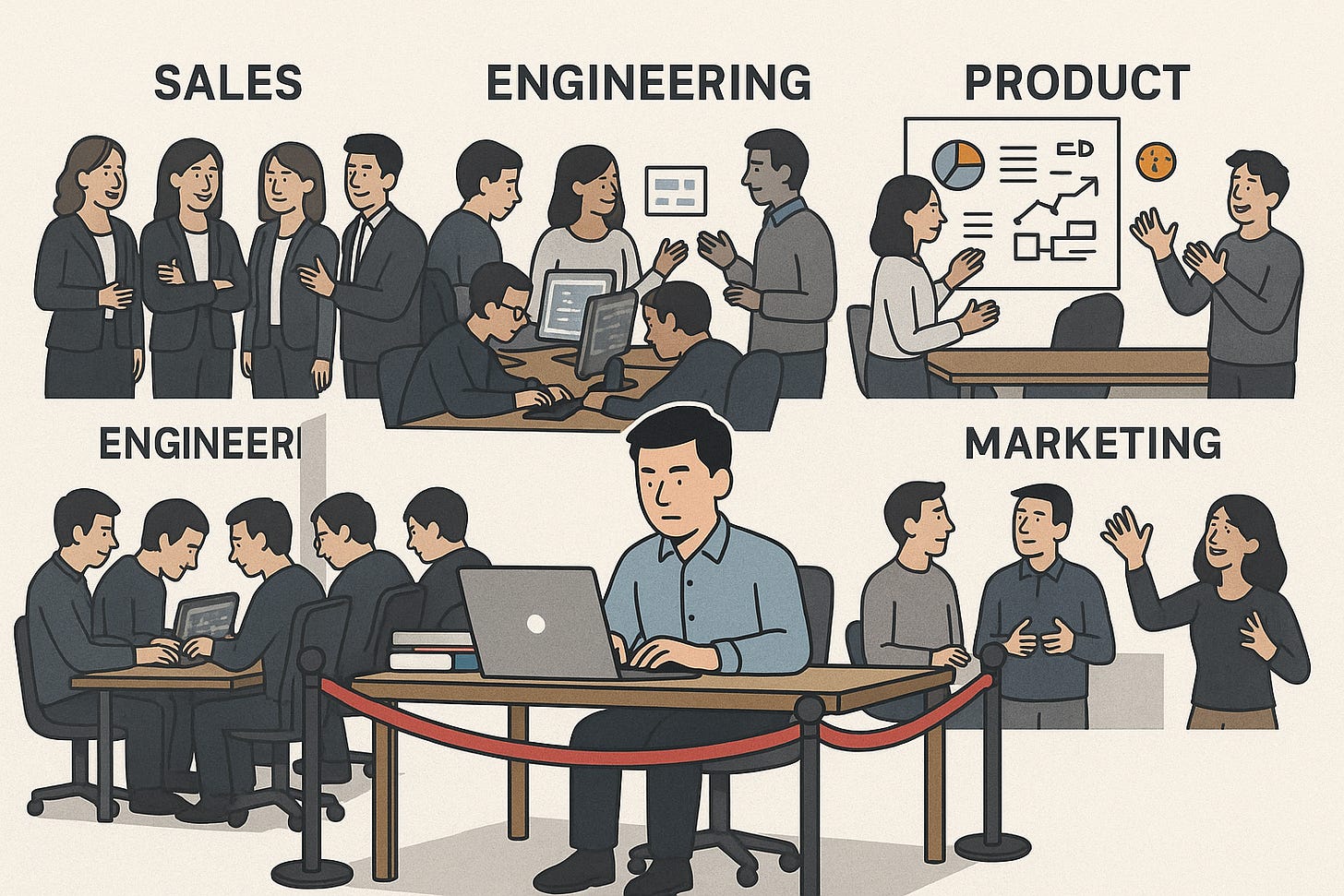

Technical writers feel this tension more acutely than most. We sit at the intersection of engineering, product, support, sales, marketing, and design. Each group has its own assumptions about what documentation is, how it should be created, and where it fits within the product landscape.

It’s easy to contort yourself to meet every one of those expectations. It feels like the responsible thing to do. However, this is erosion by accommodation. And you can address this by designing the environment around you to support the shape you’ve already defined.

I saw this clearly during a conversation with a young writer named Mike. He was a few months into a new role and already underwater.

“Hey Mike, how’s the writing coming along for the security feature release?”

“Kevin,” he said. “I’m chasing JIRA tickets. I’m reading Slack threads. I’ve had multiple meetings with engineers, and somehow I feel like I understand less than when I started.”

I nodded. “So... what’s your next move?”

He sighed. “I’m going to build my own demo, start to finish, and test the security flow myself.”

Mike thought he needed more grit and perseverance. What he needed was to define his environment. I used to operate the same way. Sometimes I still catch myself doing it. But there’s a better approach that doesn’t rely on personal heroics.

I told him something simple:

“Have the engineers and PMs write the foundational draft.

They give you the marble slab.

You carve the statue.”

He looked surprised. Maybe even relieved.

Environment design isn’t about control. It’s about structural clarity:

Engineers provide the technical intent.

PMs provide the rationale, constraints, and narrative.

Writers refine for clarity, sequence, and tone.

This is the second half of resilience.

The Quiet Conclusion

Technical writing will always expose you to volatility. It will appear as shifting features, incomplete inputs, unclear ownership, timelines that compress, or feedback that arrives too late.

But when you’ve defined yourself and designed an environment that reinforces that definition, the volatility stops being existential. It becomes part of the landscape you’re built to move through.

Resilience isn’t earned through endurance. It’s protected through structure.

Everything else is just noise testing the shape.